Seattle General Strike

Feb 6-11, 1919

Seattle, Washington

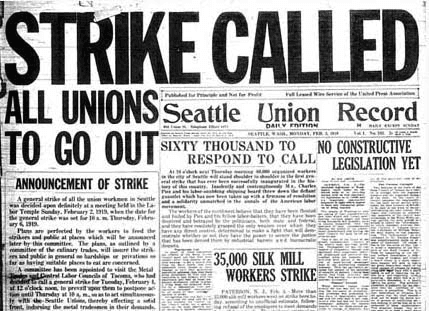

When Seattle fell silent on the morning of February 6, 1919, no American city had ever witnessed anything quite like it. Over 60,000 workers walked off their jobs simultaneously, shutting down an entire metropolitan area through coordinated action rather than violence. For five days, working people would demonstrate their capacity to shut down a city and operate its essential services themselves.[1],[2]

The conflict grew from the pressures of war. Seattle had transformed during World War I into an industrial powerhouse, its shipyards working around the clock to feed the war machine. Manufacturing output surged from $64.5 million in 1914 to $274.4 million by 1919, and union ranks swelled alongside it, growing from 15,000 to 60,000 members.[1] But workers who built the ships that won the war returned to find their wages had not kept pace with soaring prices, while the housing shortage made finding a decent place to live nearly impossible.

The immediate spark was a wage dispute in the shipyards. Federal wage controls during the war had left Seattle workers earning significantly less than their counterparts in other cities, a gap they calculated at 22.5 cents per hour.[1] When 35,000 shipyard workers from Seattle and Tacoma walked out on January 21, 1919, demanding $8 daily for mechanics, $7 for specialists, and $6 for helpers, the federal government responded not with negotiation but with threats.[1],[6] Charles Piez of the Emergency Fleet Corporation warned he would cut off steel supplies and cancel contracts if employers met worker demands, effectively blocking any path to resolution.[6]

What happened next surprised everyone, including the strikers themselves. The Metal Trades Council asked other unions to join them, and the response exceeded all expectations.[6] Union after union voted yes until 110 AFL locals had committed to walk out together, bringing the total number of participants close to 100,000.[6] A strike committee of roughly 300 delegates, most of them ordinary workers with no formal leadership training, took on the task of coordinating an entire city's shutdown.[6] On the morning of February 6, Seattle went quiet. Streetcars sat motionless in their barns. Stores locked their doors. As one striker recalled years afterward: "Nothing moved but the tide."[3]

The strike revealed something authorities had not anticipated: workers could run a city as well as shut one down. Eight blocks from City Hall, where Mayor Ole Hanson and business leaders anxiously monitored events, the Labor Temple became the nerve center of an alternative civic administration.[3] Communal kitchens opened across the city, serving roughly 30,000 meals each day.[6] Milk wagon drivers ensured that hospitals and families with infants still received deliveries. Laundry workers kept hospital linens clean. Garbage collectors focused on removing anything that posed a public health risk.[6] An Executive Committee of Fifteen reviewed requests from city departments for exemptions, deciding case by case which services truly could not be interrupted.[6] The strikers had moved beyond protest to demonstrate an alternative vision of how a city might function.

Order on the streets came not from police but from the strikers themselves. Unarmed veterans wearing labor armbands patrolled neighborhoods, encouraging residents to remain calm.[3] The AFL unions who organized the strike maintained discipline, though members of the more radical Industrial Workers of the World and Japanese laborers also participated.[6] Japanese workers received representation on the strike committee, albeit without voting privileges, an arrangement whose precise reasoning the historical record does not fully explain.[6] Mayor Hanson positioned two Army battalions in the city and threatened martial law, but no violence occurred. The silence that settled over Seattle was not the silence of fear but of purposeful restraint.[3]

Opponents immediately blamed the Industrial Workers of the World, the radical union known as the Wobblies, casting the strike as a Bolshevik revolution in American clothing.[2] The reality was more complicated. Strike leaders like James Duncan denied that the IWW played any organizing role, and the Wobblies' own newspaper stopped short of claiming credit while applauding worker solidarity.[2] Historian Colin Anderson concluded that the truth fell somewhere between these accounts: individual IWW sympathizers certainly joined the walkout, but the organization as such operated in the background rather than directing events.[2] Seattle's strike was part of a larger national upheaval; across America in 1919, more than four million workers would participate in strikes of various kinds.[6]

The strike's end came not from suppression but from internal pressures. Mayor Hanson, who had initially cooperated on essential services, shifted to ultimatums, demanding workers return by Saturday under threat of martial law.[6] The Executive Committee recommended ending the action by a vote of 13 to 1, but rank-and-file delegates on the full Strike Committee rejected that advice and voted to continue.[6] What finally broke the strike was a combination of pressure from national union leadership and the sheer difficulty of sustaining a closed city indefinitely.[6] Unions began returning to work one by one, streetcar operators and teamsters among the first. By Monday, February 10, five days after it began, the general strike was effectively over, though shipyard workers held out longer on their original demands.[6]

The aftermath brought repression rather than reconciliation. Police raided the IWW hall and Socialist Party headquarters, arresting leaders and temporarily shuttering the Union Record, the labor-friendly newspaper that had covered the strike.[3] National press coverage framed Seattle as a revolution defeated, and Mayor Hanson emerged as the hero of that narrative, proclaiming that Americanism had crushed Bolshevism.[4] His fame proved fleeting. Hanson resigned in August 1919 to cash in on his celebrity through a speaking tour that reportedly earned him $40,000, but public interest in his story had evaporated by the following year.[4]

The shipyard workers never won their wage demands, yet the strike's significance outlasted its immediate failure. For five days, ordinary workers had demonstrated that they possessed the organizational capacity to halt a modern city and keep its essential functions running on their own terms. Later labor historians would describe Seattle 1919 as the American general strike that came closest to genuine worker self-management, both in its philosophy and its practice.[6] The movement's decline owed much to economic forces beyond anyone's control. Seattle's shipyards closed within a year, scattering the workforce that had made the strike possible, and the cooperative businesses workers had established collapsed in the recession of 1920-21.[6]

The patterns established in 1919 echo through subsequent American history. Mayor Hanson's framing of labor activism as foreign-inspired radicalism would become a recurring theme, deployed against union organizers throughout the twentieth century and resurfacing whenever protest movements challenge established power. The Red Scare tactics that followed the strike, with raids on radical organizations and arrests of suspected subversives, anticipated the McCarthy era three decades later. Yet the strike also demonstrated possibilities. The idea that workers could organize essential services themselves, that solidarity across craft lines could shut down an entire economy, influenced labor movements for generations. Seattle itself would remain a union stronghold, its progressive political culture traceable in part to the networks forged during those five days in February. The city that later became home to Boeing, Amazon, and Starbucks carries a labor history that shaped its identity as much as any corporation. When Seattle workers staged a general strike again in 1999, disrupting the World Trade Organization meetings, they consciously invoked 1919, proving that the memory of what workers once accomplished had not entirely faded.

Sources

- [1] Webb, Patterson. "Seattle Shipyard Workers on the Eve of the General Strike." Seattle General Strike Project, Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, University of Washington. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/strike/shipyards_webb.shtml (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [2] Anderson, Colin M. "The Industrial Workers of the World in the Seattle General Strike." Seattle General Strike Project, Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, University of Washington, 1999. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/strike/anderson.shtml (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [3] Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, University of Washington. "Seattle General Strike Project." Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/strike/ (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [4] Williams, Trevor. "Mayor Ole Hanson: Fifteen Minutes of Fame." Seattle General Strike Project, Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, University of Washington. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/strike/williams.shtml (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [5] Ostrander, Lucy. Witness to the Revolution: The Story of Anna Louise Strong. Stourwater. Available at: https://youtu.be/efM5EsZPfbA (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [6] "The Seattle General Strike of 1919." Libcom.org. Available at: https://libcom.org/article/seattle-general-strike-1919 (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [7] "The Revolutionary Legacy of the 1919 Seattle General Strike." Revolutionary Communists of America. Available at: https://communistusa.org/the-revolutionary-legacy-of-the-1919-seattle-general-strike/ (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [8] Anderson, Colin M. "The Industrial Workers of the World in the Seattle General Strike." Libcom.org. Available at: https://libcom.org/article/industrial-workers-world-seattle-general-strike-colin-m-anderson (Accessed November 5, 2025).