San Francisco Earthquake and Fire

April 18, 1906

San Francisco, California

San Francisco in 1906 stood as the unrivaled metropolis of the American West, a city whose rapid growth from Gold Rush outpost to financial powerhouse seemed unstoppable. Then, before dawn on April 18, the earth itself challenged that assumption. What followed over the next three days would reshape the physical city and force Americans to reckon with urban vulnerability in ways they had never before considered.[1]

A policeman patrolling the early morning streets witnessed something that defied comprehension: "I could see it actually coming. The whole street was undulating. It was as if the waves of the ocean were coming toward me."[1] The ground itself had become liquid, rolling in visible waves as the San Andreas Fault tore open along nearly 270 miles of the California coast.[5] Scientists would later calculate that the fault plates shifted at speeds approaching 1.7 miles per second, generating a magnitude 7.9 shock that rippled outward from an epicenter just offshore.[5] The tremor rattled windows from Oregon to Los Angeles and reached as far inland as Nevada.[1]

The earthquake revealed a hidden truth about San Francisco's geography: much of the city rested on unstable foundations. Neighborhoods built atop former marshlands, creek beds, and filled-in sections of the bay experienced the worst destruction as the saturated soil lost its solidity, a phenomenon scientists call liquefaction.[1] The Valencia Street Hotel in the Mission District illustrated this danger most horrifically when the ground beneath it gave way, collapsing the building and trapping approximately 50 residents inside.[5] Meanwhile, areas built on bedrock, such as Pacific Heights, emerged with little more than cracked chimneys.[5] This stark contrast between neighborhoods demonstrated how the city's hasty expansion had created zones of unequal risk, with working-class districts often occupying the most hazardous terrain.

The earthquake itself became a lethal test of construction methods. Unreinforced brick and masonry structures crumbled throughout the city, their walls collapsing into the streets below. Chimneys proved particularly deadly, toppling through roofs onto sleeping residents. Among the victims was San Francisco's fire chief, killed in his bedroom by falling brickwork, a loss that would prove catastrophic in the hours ahead.[1] Conversely, the city's newer steel-framed buildings demonstrated the value of modern engineering, absorbing the shock without structural failure.[1] Wooden buildings presented a mixed picture: those built on solid ground generally survived, while those on filled land shifted off their foundations entirely.[1]

South of Market Street, where wooden tenements housed much of the city's working population, the earthquake proved doubly fatal. The same liquefaction that swallowed buildings also trapped their occupants inside, and what the collapsing structures did not kill, the fires soon would.[1],[2] Hundreds, possibly thousands, of residents found themselves buried alive as the ground transformed into something resembling quicksand.[2] Rescuers who rushed to help discovered an impossible situation: even as they dug through rubble, flames spread from ruptured gas mains and ignited the debris around them, forcing them to abandon people they could still hear calling for help.[2]

The city's firefighters faced a cruel irony. The same seismic forces that created the emergency had also destroyed their ability to respond to it. Water mains lay shattered beneath the streets, rendering hydrants useless precisely when they were needed most.[1] Over the following 72 hours, the blaze grew into a self-sustaining atmospheric phenomenon. Jack London, observing from a boat in the bay, captured its terrifying physics: "It was dead calm. Not a flicker of wind stirred. Yet from every side wind was pouring in upon the city. The heated air rising made an enormous suck. Thus did the fire of itself build its own colossal chimney through the atmosphere. Day and night this dead calm continued, and yet, near to the flames, the wind was often half a gale, so mighty was the suck."[1] The conflagration had become self-perpetuating, generating its own weather system to fuel its advance.

Desperate circumstances demanded improvised solutions. General Frederick Funston mobilized Army troops from the Presidio without waiting for orders from Washington, a decision that brought both military discipline and controversy to the crisis.[1] With hydrants dry, firefighters resorted to dynamiting buildings to create firebreaks, though the explosions sometimes spread flames rather than stopping them. Near the waterfront, crews ran hoses directly into the bay. In North Beach, Italian residents turned to an unlikely resource: the neighborhood's abundant wine cellars became impromptu reservoirs, their contents splashed onto burning homes when nothing else remained.[1]

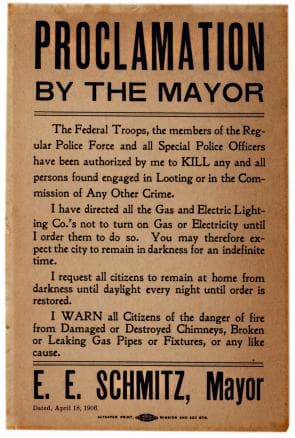

As the city burned, fear of disorder produced its own form of violence. Mayor Eugene Schmitz, already under investigation for corruption, issued a proclamation that revealed how quickly civil authority could turn draconian: "The Federal Troops, the members of the Regular Police Force, and all Special Police Officers have been authorized by me to KILL any and all persons found engaged in Looting or in the Commission of Any Other Crime."[1] The order, of questionable legality even in an emergency, sanctioned summary execution based largely on rumor. While reports of widespread looting proved exaggerated, the authorization was not hypothetical. Several people died at the hands of authorities, some likely guilty of theft, others simply in the wrong place during a moment of collective panic.[1] This pattern of exaggerated looting fears justifying extreme force would repeat throughout American history, from the deployment of National Guard troops after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to debates over policing during the 2020 protests. The 1906 response established an early template for how American authorities balance civil liberties against perceived threats to property during emergencies.

The fire's slow, relentless advance created a paradox: it allowed most residents time to escape while forcing them to watch their entire lives disappear behind them. Families streamed toward the ferries, clutching whatever possessions they could carry as they fled across the bay to Oakland and Berkeley.[1] Others retreated westward, camping in Golden Gate Park or clustering in neighborhoods the flames had not yet reached. Unlike the sudden violence of the earthquake, the fire offered the terrible gift of hours to choose what to save, to look back one last time, to understand fully what was being lost.[1]

When the fires finally exhausted themselves, they had erased the heart of San Francisco: over four square miles and nearly 28,000 buildings reduced to rubble and ash.[5] The flames made no distinctions, consuming gleaming corporate headquarters and cramped tenements alike, church steeples and red-light district brothels, a million volumes from public and private libraries.[1] Roughly 300,000 people found themselves without homes.[5] The human toll proved harder to calculate, in part because civic leaders wanted it that way. Official records documented only 498 deaths, a figure that invited investment by minimizing the catastrophe's severity.[1] Later researchers, examining morgue records and missing persons reports, concluded that between 2,000 and 3,000 people perished in the disaster and its immediate aftermath.[1],[5] Property losses reached approximately $400 million in contemporary currency, with the earthquake accounting for only $80 million of that total. Modern economists estimate that rebuilding today would cost upwards of $32 billion.[1]

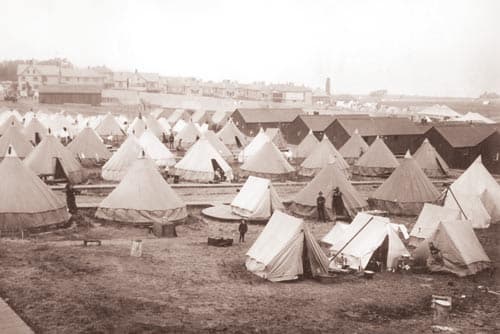

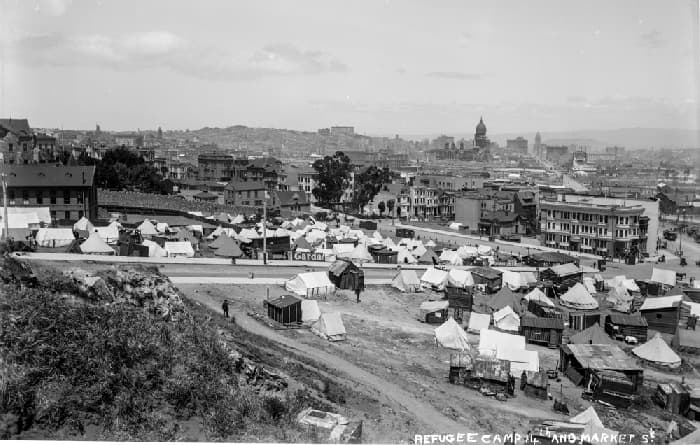

The scale of homelessness demanded a relief operation larger than any American city had ever attempted. Contributions totaling $9 million arrived from across the nation and around the world, but distributing aid to hundreds of thousands of displaced people required coordination that no American city had ever attempted.[1] Mayor Schmitz, though already facing corruption investigations, organized a fifty-member citizens' committee under former mayor James Phelan to manage the crisis.[1] The Army established twenty tent camps across the city, some on military grounds at the Presidio, others scattered through public parks. These makeshift communities would shelter refugees for more than a year.[1] Military and civilian health officials worked together to maintain sanitation and prevent the epidemic diseases that often follow disasters of this magnitude, a success that likely saved more lives than were lost in the fire itself.[1]

The ashes had barely cooled before San Francisco's commercial elite began planning their city's resurrection. Their urgency stemmed from economic anxiety: Los Angeles, Seattle, and Portland stood ready to absorb business that might otherwise return to San Francisco, threatening the city's dominance over western commerce.[1] This pressure for speed produced unlikely alliances, as business owners and union leaders who had battled for years agreed to suspend their conflicts. Yet speed came at a cost. Urban planners proposed reimagining the destroyed districts with grand boulevards and modern street layouts, a chance to build something better from the rubble. The business community rejected such visions as unaffordable delays. San Francisco would be rebuilt, but on the bones of its old street grid, a choice that prioritized rapid recovery over long-term improvement and left the city looking much as it had before the earthquake shook it apart.[1]

The earthquake's legacy extends far beyond 1906. The disaster accelerated seismic research that eventually produced California's strict building codes, making modern San Francisco far more resilient than the city that fell in three days. The competition with Los Angeles that drove the frantic rebuilding never truly ended; by the mid-twentieth century, Southern California had surpassed San Francisco as the economic engine of the West. Yet San Francisco reinvented itself, transitioning from a port and manufacturing center to a hub of finance, technology, and culture. The city that hosts Silicon Valley's venture capital firms and draws tourists to its cable cars traces its modern identity to choices made in the months after the fire. The 1906 disaster also demonstrated that California's cities sit atop active fault lines, a geological reality that shapes urban planning, insurance markets, and public consciousness to this day. Every Californian grows up learning earthquake drills, a direct inheritance from the morning the ground turned to waves.

Then and Now: 100 Years Later

Hover to compare: W.A. Coulter's 1906 painting (right) and a 2006 photograph from the same viewpoint (left).[1][5]

Sources

- [1] Cherny, Robert W. "San Francisco and the Great Earthquake of 1906." History Now: American Cities, Issue 11 (Spring 2007). The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Available at: https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/essays/san-francisco-and-great-earthquake-1906 (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [2] Hansen, Gladys. "Timeline of the San Francisco Earthquake, April 18-23, 1906." The Museum of the City of San Francisco. Excerpted from "Chronology of the Great Earthquake, and the 1906-1907 Graft Investigations." Available at: http://www.sfmuseum.org/hist10/06timeline.html (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [3] "Grim Photos of the 1906 San Francisco Quake, Mapped." Bloomberg CityLab, April 20, 2017. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-04-20/grim-photos-of-the-1906-san-francisco-quake-mapped (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [4] Saint Louis University Earthquake Center. "1906 San Francisco Earthquake Photographs." Available at: https://www.eas.slu.edu/eqc/eqc_photos/1906EQ/ (Accessed November 5, 2025).

- [5] California Geological Survey. "The Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake." California Department of Conservation. Available at: https://www.conservation.ca.gov/cgs/earthquakes/san-francisco (Accessed November 5, 2025).